The large majority of serious injury claims settle before trial, frequently in joint settlement meetings (JSMs). Rob Hunter gives consideration to several issues that often arise in discussions and searches for 'method in the mediation'.

Mediate or else

In the present climate, the pressure on parties to mediate is almost irresistible. An ADR direction along the following lines is a normal feature of case management orders:

“At all stages the parties must consider settling this litigation by any means of Alternative Dispute Resolution (including mediation): any party not engaging in any such means proposed shall serve a witness statement giving reasons [within 21 days of that proposal / not less than 21 days prior to trial].”

For over a decade, even in the absence of such a direction, winning parties have been at risk of sanctions for failing to mediate, following the landmark case of Halsey v Milton Keynes NHS Trust [2004] EWCA Civ 576. If anything, judicial attitude towards parties who decline ADR has hardened of late. For example, the wholly successful party in Christian v The Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis [2015] EWHC 371 was deprived of one-third of its costs: it was said it was “unrealistic” to suggest that a settlement by way of ADR would have been inappropriate despite the subject matter of the dispute.

In the last 9 months the NHS – being the losing party – has twice found itself on the other end of an order for indemnity costs for failure to accept an offer to mediate the costs of litigation. Anecdotal evidence suggests a greater willingness by paying parties to contest bills of costs; perhaps Reid v Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust [2015] EWHC B21 (Costs) will prove to be a deterrent.

In practice both parties generally need little encouragement to negotiate. Claimants do not relish the prospect of a trial and defendants minimise their overall liability by concluding the claim promptly.

Opening offers

The conventional view is that the aim is to secure the first offer from the other party. The theory is that if compelled to make an offer, a party will show their hand. The reality is that the first offer often gives no useful

indication of how a party sees their case. Some lawyers go so far as warning their clients that they should not take the first or second offer seriously!

The contrary view is that there can be an advantage in opening negotiations with the right figure. The phenomenon of anchoring is known to psychologists: it is the tendency to rely too heavily on the initial piece of information (“the anchor”) when making subsequent judgments. Lawyers are trained to be more sophisticated in their analysis but even so a party who seizes the initiative demonstrates confidence in their case and can set the agenda.

In my view, there is something to be said for both approaches. For example, a sensible Counter-Schedule coupled with a reasonable opening offer can provide a powerful platform for subsequent negotiations. In practice, the willingness of a party to stand firm or enter the arena by making an offer may depend on whether they feel able to stand behind an existing Part 36 Offer or Schedule.

You may also be interested in:

- Do the Robot: the impact of robotic technology in spinal injury cases - Stephen Cottrell discusses the impact of robotic technology in spinal injury cases.

- Khan v Meadows: scope of duty and damages for wrongful birth claims - Stephen Cottrell and John Platts-Mills consider the recent Supreme Court judgment of Khan v Meadows in which the SC explained the key role performed by the ‘scope of duty’ test in the law of negligence generally.

Further offers

The only unbreakable rule of JSMs is to think ahead. This is because, unless there is something very unusual about the case, there will be a number of offers from both sides.

Negotiations often follow one of the two simplified patterns shown below:

Meet in the middle

Big hop and stop

The “Meet in the middle” approach illustrates a common tendency for the gap between offers to reduce exponentially. The “Big hop and stop” involves a big move followed by limited further concessions. It can be a sign of strength. On the other hand, a party reveals more of their position at an early stage and so it can be harder for that party to reach a better-than-expected settlement. In either event, it is often worth tracking the mid-point between the parties and the size of reductions. Returning to the above examples, following opening offers of £600k and £1m, the mid-point of £800k will inevitably exert a certain gravitational pull.

Negotiating

Pick your battles

One of the important, but often overlooked, aspects of a JSM is how a party should guide the discussions in their own interests. Before entering negotiations, it is essential to analyse not only which aspects of the claim are strong or weak, but also which issues are likely to make the biggest difference to the overall award (the “sensitivities”).

The impact of some issues — for example, employment-related multipliers or distant losses — is not always intuitive: the process of number crunching may reveal an impact that is more or less significant than may first appear.

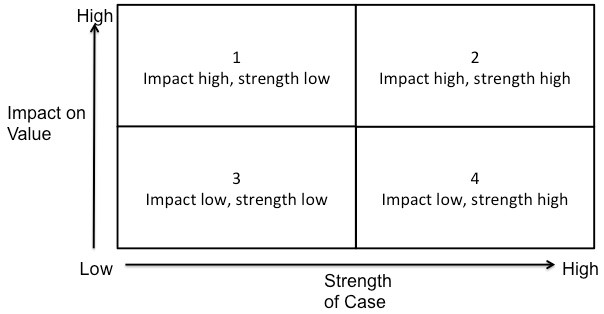

The following diagram illustrates the two layers of analysis:

Having identified the sensitivities of the case in advance, a party can plan their negotiation strategy. Discussions should normally be focused on issues in box 2 where the party’s position is strong. At the same time, representatives need to be ready to fight their corner on issues in box 1. Concessions should be avoided as far as possible on box 1 issues even if, privately, a party perceives vulnerability. If a concession is to be made, it is preferable to make it on an issue in box 3. Irrespective of whether a party is strong or weak on a particular sensitivity, it is worth reflecting on how the client’s case can be put best in a nutshell.

Breaking it down

There is no obligation on a party to provide a breakdown of the individual awards that make up an offer. There can be an element of artifice in doing so since it is usually possible to come up with a set of figures that support a variety of awards. One of the disadvantages of providing a breakdown is that it can reveal quite a lot about a party’s position. It is worth bearing in mind that it is impossible to know for sure where the opposing party perceives risk. A breakdown can, however, be useful in breaking a deadlock. For this reason, it is suggested that the exchange of figures is often useful nearer to the end of a JSM than the beginning.

Who does the talking?

The normal method of negotiation is counsel-to-counsel or claimant’s counsel to defendant’s solicitor. However, this is not always appropriate. It can be helpful, for example, for an insurer to hear how the claimant comes to their figures.

Listen and learn

If the JSM does not bring about settlement, it should be used to gain the best understanding of how the case against your client will be put. Based on observations made during the meeting, it is worth taking stock before the meeting ends to identify any further evidence or steps that are needed to strengthen the case and meet the points made against you.

Final offers

More than in any other part of the meeting, there is a tendency for the final stages of the JSM to involve a degree of gamesmanship. It is often the case that both parties have a range in which they are willing to settle and where the case is compromised within that range can be determined in the final exchanges. It is impossible to offer universal guidance but some thoughts are given below:

It may not be helpful for claimants to make clear their bottom line since this can become a figure for the defendant to chip away at.

Defendants need to have in mind that claimants will be looking to make sure they have reached the absolute maximum figure the defendant’s insurer (or the NHSLA, as applicable) is prepared to offer. It is sometimes necessary to be brave: if the meeting breaks down, there is generally scope for further written offers.

If the motivation to settle is genuine, it is suggested that it will usually be appropriate for both parties to make final offers that are slightly more generous than the Part 36 Offer they intend to make. That serves to provide a genuine settlement premium by redistributing the costs that have been saved. There is no reason why the level of Part 36 that is intended should not be conveyed to the other party.

Parting on good terms

It goes without saying that that although the aim is to settle, it is not to settle at any cost. There is no duty to compromise, despite what some judges appear to think.

Much more can be said but some secrets must remain secret.

Until we next exchange offers, many happy negotiations…

Rob Hunter has recognised expertise in high value personal injury claims arising from serious injury or fatality. He is ranked as a leading junior for PI by both Chambers UK and Legal 500.

Follow Devereux on Twitter and LinkedIn for up to date personal injury and clinical negligence news.

Back to blog

Additional Information

All Blogs

Archive

- November, 2025

- May, 2025

- February, 2025

- January, 2025

- November, 2024

- September, 2024

- June, 2024

- April, 2024

- March, 2024

- December, 2023

- July, 2023

- May, 2023

- April, 2023

- March, 2023

- February, 2023

- May, 2022

- March, 2022

- February, 2022

- November, 2021

- October, 2021

- September, 2021

- August, 2021

- July, 2021

- June, 2021

- May, 2021

- March, 2021

- February, 2021

- November, 2020

- October, 2020

- September, 2020

- August, 2020

- June, 2020

- May, 2020

- April, 2020

- March, 2020

- February, 2020

- November, 2019

- October, 2019

- August, 2019

- July, 2019

- June, 2019

- May, 2019

- March, 2019

- February, 2019

- January, 2019

- December, 2018

- October, 2018

- September, 2018

- July, 2018

- June, 2018

- May, 2018

- April, 2018

- February, 2018

- December, 2017

- November, 2017

- October, 2017

- July, 2017

- June, 2017

- May, 2017

- April, 2017

- March, 2017

- February, 2017

- January, 2017

- June, 2016

- May, 2016

- April, 2016

- March, 2016

- February, 2016

- December, 2015

- November, 2015

- July, 2015

- March, 2015