On 27 February 2016, the Ministry of Justice announced the first change to the discount rate after sixteen years.

The new rate of minus 0.75% took effect on Monday 20 March 2017. So far, it is unchanged but few are holding their breath.

The announcement had an immediate impact with claimants scrambling to withdraw or amend existing offers and defendants urgently considering whether such offers should be accepted.

Now that the dust has settled, the time is right to look into the mind of the Lord Chancellor, set aside thoughts of dairy products and trade deficits, and ask: What next? Why me? And was it something I said?

Was it something I said?

The Lord Chancellor’s announcement sent shockwaves through the legal and insurance world. Strong views reverberated back.

Huw Evans, Director General of the Association of British Insurers, said this:

“Cutting the discount rate to -0.75% from 2.5% is a crazy decision by Liz Truss. Claims costs will soar… We estimate that up to 36 million individual and business motor insurance policies could be affected in order to over-compensate a few thousand claimants a year.

“To make such a significant change to the rate using a broken formula is reckless in the extreme, and shows an utter disregard for the impact this will have on consumers, businesses and the wider operation of the insurance market.”

APIL’s press release was as follows:

People who suffer severe life-changing injuries can now be assured that the compensation needed to look after them is calculated correctly and is sufficient to provide care for the rest of their lives…

But we must also note that this change is long overdue. People already coping with the most severe injuries have been deprived of the help and care they need for years. Meanwhile insurance companies, which have saved millions of pounds in unpaid compensation, have been aware that a decision to change the discount rate has been on the cards for six years… and the fact that many are now saying premiums will have to rise to cover the cost simply beggars belief.

The truth is that the change in the discount rate has had a dramatic impact on nearly all claims with a future loss element.

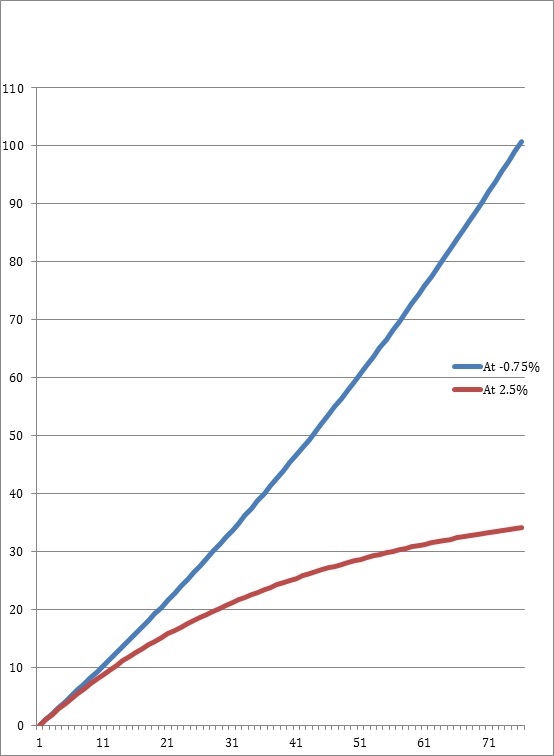

The following graph shows the divergence in Table 28 multipliers at 2.5% and minus 0.75% over the course of 80 years (x-axis - years; y-axis - multiplier).

Several examples from the supplementary Odgen Tables published by the Government’s Actuary’s Account help to illustrate the point.

In accordance with a negative discount rate, the discount for accelerated receipt becomes an enhancement. At 2.5%, £975.61 would be awarded today to compensate for the loss of £1,000 in a year. At -0.75%, £1,007.56 would be awarded.

The longer the period of loss, the larger the impact. Thus, the life multiplier for a man aged 45 at 2.5% is 24.70; at minus 0.75%, it is 48.34. The overall increase is 96%, so claims capitalised with this multiplier are worth nearly double.

A young claimant would see the most dramatic difference. For a girl of 10, the life multiplier at 2.5% would be 34.75. At minus 0.75%, it is 114.70. This is an increase of 230%.

Of course, these increases do not provide an accurate indication of the increase in the overall value of the claim. The main factors are the proportion of past losses to future losses and the losses taken as a PPO as opposed to a capitalised sum.

As a rule of thumb, in the context of an article worth reading in its entirety, Kennedys suggest that the average age bracket of a claimant is 30-40 and in such cases, the percentage of future losses to the overall claim is around 80-90%. On the face of it, this proportion could be expected to increase.

Of course, this may overstate the significance of the change. In the largest claims, a periodical payment order is (or, at least, it was) at the front of the parties’ minds for the largest heads of loss. Except where liability is in issue, in the past, it was a brave claimant who elected to take a lump sum for all losses.

Why me?

Under The Damages Act 1996, the Lord Chancellor has the power to set the discount rate. However, the rate had remained unchanged since the power was last exercised by Lord Irvine of Lairg in 2001 in the Damages (Personal Injury) Order 2001 (S.I. 2001/2301).

In setting the new rate, the Lord Chancellor issued a written statement that set out a conservative approach to her powers.

She concluded that “a faithful application” of the majority view in Wells v Wells led to the conclusion that a portfolio of 100% index-linked gilts (ILGs) was the best measure of the return claimants could be expected to obtain. For those needing a refresher, the principles in Wells v Wells were full compensation and risk-free investment.

As such, Ms Truss professed herself unpersuaded by arguments that reference to index-linked gilts (“ILGs”) was not the “realistic or appropriate” basis since use of mixed portfolios incorporated an element of risk. She did, however, acknowledge that those arguments had some merit.

What are ILGs? In simple terms, they are IOUs issued by the government to finance government spending. They are index-linked because their yield is calculated with reference to the PRI.

Why are ILGs so low risk? Although the national debt is a subject of concern, the UK government has never technically defaulted on its debt. In other words, it has always paid the interest due on its debt, and it has always repaid the original loan back when government bonds mature (i.e. when the IOU is due).

In order to estimate the likely yield from ILGs, Ms Truss took a three-year simple average of gross real redemption. As at December 2016, this was -0.83%, which Ms Truss rounded to -0.75%. Like her predecessor, Ms Truss excluded stocks with less than five years maturity.

Why such a dramatic shift in the rate? Because there has been a steady decline in gilt yields, which have fallen since the financial crisis and, at the time of writing, have shown no signs of rising again.

What Next?

The statement issued by the Lord Chancellor recognised the impact her decision would have and sought to pour oil on troubled waters with the simultaneous announcement of a review of the framework “to ensure it remains fit for purpose”. The promise is that the consultation will start before Easter.

The consultation will cover:

“[W]hether the rate should in future be set by an independent body; whether more frequent reviews would improve predictability and certainty for all parties; and whether the methodology - which in effect assumes that claimants would invest only in index-linked gilts - is appropriate for the future. Following the consultation, which will consider whether there is a better or fairer framework for claimants and defendants, the Government will bring forward any necessary legislation at an early stage.”

This bears more than a passing resemblance to the consultation that closed more than 4 years before the Lord Chancellor’s decision was announced.

Those with long memories will remember that in November 2010 a review was announced following a letter of claim under the pre-action protocol for judicial review. Judicial Review proceedings were commenced by APIL in April 2011.

The consultation on the methodology to be used, Damages Act 1996: the discount rate – how should it be set, was eventually published on 1 August 2012 and closed on 23 October 2012.

There were two parts to the earlier consultation. Some insight into the government’s position then and now may can be gained by looking at the “overview” document issued at the time.

The first part of the consultation raised a question in relation to the methodology. It was suggested that many claimants did not invest in the cautious way envisaged by the existing “risk free” guidelines. It was suggested that might mean that rate was too low. The options under consideration were to retain the current Wells approach or set the rate by reference to investment strategies which may produce higher returns at the expense of higher risk.

The second part of the consultation asked whether there was a case for encouraging the use of periodical payments. The Government expressed a wish to see PPOs as the norm in future loss cases. BLM suggests market data shows that still only roughly a third of cases over £1m settle with a PPO.

On 8 March 2017, the Ministry of Justice summarised the result of the previous consultation as follows:

“Widely diverging views were expressed by different interest groups, and overall the responses demonstrated very little consensus on the methodology which should be used in setting the rate or on the technical considerations which should be applied to that process.”

As a result, Chris Grayling, the previous Lord Chancellor sought help. In 2015, a panel of experts was appointed to consider the responses to the consultations and advise the then Lord Chancellor on the rate review.

They reported in October 2015 but the report was published for the first time on 8 March 2017. The panel concluded (p109):

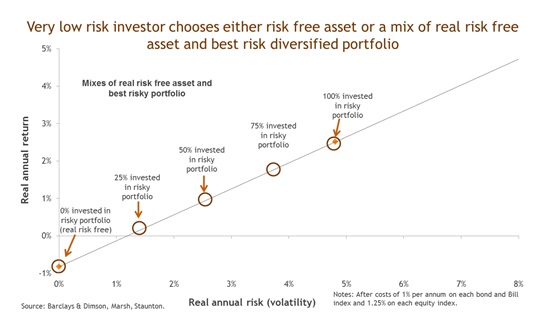

Assuming that ILGS are virtually investment risk free, an investor with a very low appetite for risk will find an appropriate combination of ILGS and the optimal mix of risky investments.

A very low risk investor might put one-half, 50%, into ILGS and one-half into the best risk portfolio, or three-quarters, 75%, into ILGS and one-quarter into the best risk portfolio

The panel produced a graph that summarised the expected rate of real return depending upon the amount of risk that the investor was prepared to tolerate:

Where Now?

Few believe that the negative 0.75% rate will remain in the long term.

In the meantime, there will be a window in which claims coming on for trial will have a significantly higher value. The question for practitioners is how long that period will last and what will the rate become.

The Window

There is implicit recognition in the Lord Chancellor’s announcement that change will require legislation. That is surely the position.

In the past, the process of consultation has moved slowly. No doubt the government will be more highly-motivated to address the issue this time around. It is obvious that current economic and political implications of the decision are at the forefront of the Lord Chancellor’s mind. NHS Trusts and the MoD have a great deal to lose by a reduced discount rate. The current reduction in the discount rate will encourage claimants towards lump sum awards that the NHSLA can ill afford.

On the other hand, the Ministry of Justice has its hands full.

The ABI has lobbied for a provision to be included in the Prison and Courts Bill with a view to the rate to be changed again before the end of the year:

“It is a challenging but reasonable ask from the insurance industry to the government to carry out an urgent consultation, to take a decision to change the law, to take that through Parliament, and having done that, a new rate to be set by the end of the year.”

A much better estimate of the timetable will be possible when the government publishes the consultation that is promised imminently. The form of the consultation will be instructive: for example, there may be a specific proposal; alternatively, there may be a further call for evidence.

For the moment, it is suggested that the ABI’s call for a change in 2017 is overly optimistic. On a best-guess basis, trials coming on within 18 months are likely to be determined at the present rate. Tactical manoeuvrings at CMCs can be anticipated with this in mind.

Reading the Runes

Over 16 years having elapsed without any adjustment of the rate to changed economic circumstances, it is difficult to believe that the government will conclude that claimants should be able to invest without risk. As illustrated by the recent change, permitting claimants to do so is at the expense of the NHS and the insured population, which is unpopular.

All that has emerged in previous consultations and in recent remarks suggests that the government is inclined to move away from the principles established in Wells v. Wells.

There were rumours previously that the government was looking at the approach of the Court of Protection. The government is likely to find that the long-term investment behaviour of those compensated is, in practice, not to invest in index-linked gilts. Against that, it might be said that at 2.5%, claimants had little choice.

According to the ABI, the discount rate in Europe is typically between 1% and 4%.

In theory, all options are open to the government. For example, it would be possible to impose varying rates for different losses, for example care or earnings-related losses. Alternatively, the rate could vary by periods, for example one rate for periods less than 10 years and a different rate for losses lasting more than 10 years. The latter would find support in investment practice, which would suggest that longer-term investors can afford to tolerate greater risk with a view to greater returns.

It is doubtful, in the writer’s view, that “more frequent reviews would improve predictability and certainty for all parties” as was mooted by the Lord Chancellor.

Those with suspicious minds will anticipate a process of reverse engineering with the government aiming to come to a more acceptable rate.

There is a general feeling amongst the profession that a rate in the region of 1% can be anticipated. Such a rate draws support from the expert panel’s report that suggested this could be expected with a portfolio divided equally between ILGs and a mixed basket of investments.

Conclusion

For the moment, all that can be said with confidence is that the current uncertainty surrounding the discount rate looks set to continue.

In the short term, the dynamics of large claims will reverse. The balance of benefit and disadvantage of a PPO will turn on its head with defendants encouraging the use of PPOs. Likewise, it may be defendants who seek provision for renegotiation in the event of a change in the rate in 2018.

Rob Hunter has recognised expertise in high value personal injury claims arising from serious injury or fatality. He is ranked as a leading junior for PI by both Chambers UK and Legal 500. For more information on his latest case highlights or Devereux’s leading personal injury and clinical negligence team, please contact our practice managers on 020 7353 7534 or email clerks@devchambers.co.uk.

Follow us on twitter on @devereuxlaw.

Back to blog

Additional Information

All Blogs

Archive

- November, 2025

- May, 2025

- February, 2025

- January, 2025

- November, 2024

- September, 2024

- June, 2024

- April, 2024

- March, 2024

- December, 2023

- July, 2023

- May, 2023

- April, 2023

- March, 2023

- February, 2023

- May, 2022

- March, 2022

- February, 2022

- November, 2021

- October, 2021

- September, 2021

- August, 2021

- July, 2021

- June, 2021

- May, 2021

- March, 2021

- February, 2021

- November, 2020

- October, 2020

- September, 2020

- August, 2020

- June, 2020

- May, 2020

- April, 2020

- March, 2020

- February, 2020

- November, 2019

- October, 2019

- August, 2019

- July, 2019

- June, 2019

- May, 2019

- March, 2019

- February, 2019

- January, 2019

- December, 2018

- October, 2018

- September, 2018

- July, 2018

- June, 2018

- May, 2018

- April, 2018

- February, 2018

- December, 2017

- November, 2017

- October, 2017

- July, 2017

- June, 2017

- May, 2017

- April, 2017

- March, 2017

- February, 2017

- January, 2017

- June, 2016

- May, 2016

- April, 2016

- March, 2016

- February, 2016

- December, 2015

- November, 2015

- July, 2015

- March, 2015